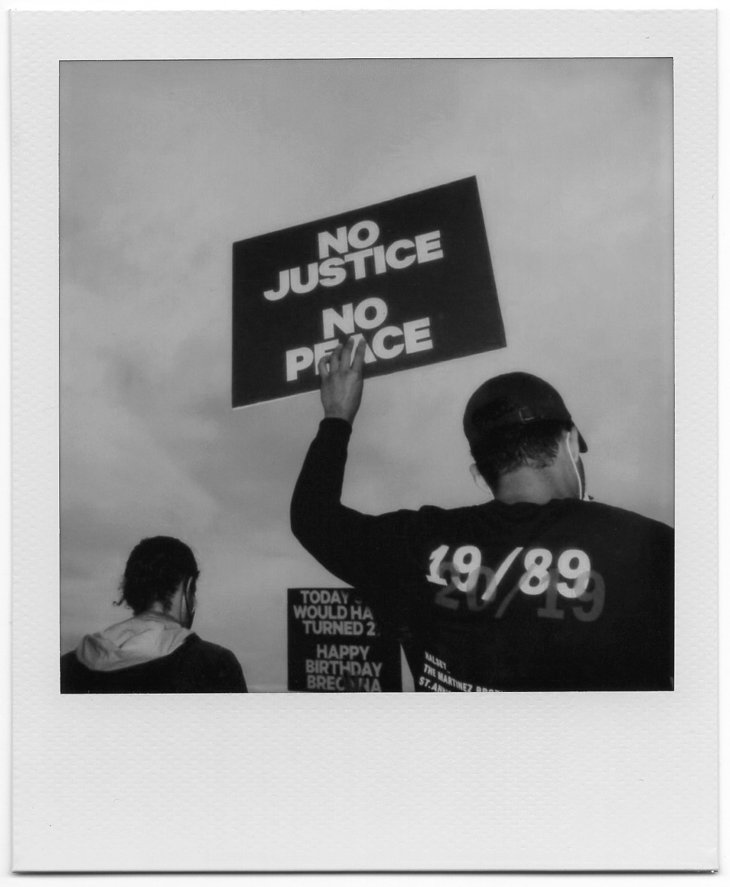

Minneapolis, MN. CHANDAN KHANNA/AFP via Getty Images

While covering the protests in memory of George Floyd in Minneapolis, journalist Linda Tirado was hit by a rubber bullet. Despite donning goggles – an increasingly common practice to protect protesters from the use of tear gas and pepper spray, two other forms of LLWs – those slid from her face until something hit her. She told the New York Times, “I immediately felt blood and was screaming, I’m press! I’m press!”. Protesters carried her out, and she was operated on within the hour. The rubber bullet that hit her damaged the vision in her left eye beyond recovery. She testified before Congress shortly after, on the violence against journalists during protests. While less-lethal weapons (LLWs) are not prohibited under international human rights law, their use has long been debated and demands compliance with the principles of necessity and proportionality. As both are routinely violated, due to local and national interpretation of what constitutes both necessity and proportionality, in addition to the discretion granted to law enforcement officers in the pursuit of their duties, the United Nations’ Officer of the High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR) released a guidance in 2020 that framed their use. This guidance has proven either ignored or too vague in a matter of months. The history of rubber bullets in crowd control is not new; from Northern Ireland to the United States, this aims at initiating a conversation that will hopefully lead to a ban on the use of rubber bullets as a dispersion method, arguing it could easily cross the threshold of cruel and indiscriminate treatment.

What’s a rubber bullet?

The rubber bullet is part of kinetic impact projectiles (KIPs) and can be made of rubber or plastic. Their role as less-lethal weapons – and not non-lethal weapons, as has been seen in various media outlets – is principally as a dispersion method during a riot or a violent assembly. The British Army developed wooden, plastic, polyvinyl chloride (PVC) then rubber bullets for use in Northern Ireland. They are solid and can be spherical or cylindrical projectiles of various sizes. Some are made of a composite that includes metal. They are to be differentiated from pellet rounds, which are closer to an actual bullet, as cartridges made from lead (or plastic, or rubber) pellet that spread when fired. Their goal is to cause physical harm, inflict pain and incapacitate an individual, without causing the degree of pain that would become a violation of the prohibition of torture. It is unclear where the threshold on the infliction of pain would lie if the projectile is fired from too close a range or is hitting a part of the body that is susceptible to be severely damaged. Firing into a crowd makes it impossible to reach those standards.

Washington, DC. Photo: REUTERS / Jonathan Ernst

UN guidance

The UN guidance aims at providing a comprehensive human rights understanding of the role of policing, in a balance between upholding law and order and minimizing risks to the human body. It acknowledges the necessity for law enforcement to be equipped with some sort of weaponry, but not necessarily use of lethal force, thus the category of less-lethal weapons”. The distinction to be made between the designated term and the colloquial mistake of referring to them as “non lethal” is a recognition that misuse could cause injury and death. The very preamble to the guidance, which is not targeted at individual officers or single police departments, but instead provides guidelines for states, traces the history of this equipment:

extrajudicial killings and acts of torture or other forms of cruel, inhuman, or degrading treatment or punishment—serious violations of international law —have been perpetrated using less-lethal weapons and certain forms of related equipment.

Recognizing the failures of the 1990 Basic Principles to abide by human rights law standards, especially in the training of police officers and in the risk assessment posed by those weapons, was at the origin of those guidelines. Minimizing risk should always take into consideration that refraining from using the weapon is at times the only way to avoid the risk altogether. Paragraph 2.3 states that

Any use of force by law enforcement officials shall comply with the principles of legality, precaution, necessity, proportionality, non-discrimination, and accountability.

As we can see through the use of qualified immunity in the United States but elsewhere, accountability is few and far-between and precaution is often discarded to the benefit of an assessment of necessity that is left to the discretion of the officer. In a tense climate in which protesters are presented as the enemy, a threat to the state, and triggering a politicization of conflict language, necessity seems to trump legality, proportionality, and much too frequently, the principle of non-discrimination, leading to the significant number of injuries that are reported. While the issue of accountability deserves its own article, it is worth noting that the United Nations Department of Peacekeeping Operations has prohibited the use of rubber bullets by UN personnel, precisely because of the risks of serious injury or even death due to improper use. The “circumstances of potentially unlawful use”, meaning the cases in which the use of the LLWs place individuals at risk of death or serious injury, which can constitute torture, are supposed to be avoided by acquiring weapons that have been tested to operate at their minimal capacity, and be subjected to thorough training in their use. Each police department operates on a different basis and it is extremely rare to see the use of human rights language and standards in law enforcement training, especially in states that seldom recognize the supranational nature of international legal standards.

Los Angeles, CA. .(Ringo H.W. Chiu/AP)

The guidance is firm in its belief that law enforcement has a legitimate purpose; one that encompasses the facilitation of peaceful assembly. Increasingly, states have empowered their police departments with counter-terrorism powers and military equipment through legislation that saw any assembly demanding political change as a potential insurgency, as opposed to the freedom of expression; has used those weapons against members of the press, in violation of the freedom of information; and against legal observers, in violation of the protection of human rights defenders. Assemblies, some of which have the potential to become a significant, historical civil rights movement have received the support of the High Commissioner, 66 Special Rapporteurs, and have been the subject of an urgent debate during the 43rd session of the Human Rights Council. If the guidance is to be followed, its definition of undue risk – a level of identifiable risk that is unacceptable – can’t be compatible with the use of KIPs and especially not rubber bullets. The case of Northern Ireland is a direct example.

Northern Ireland

Francis Rowntree was an 11 year old student at St Finian’s Primary School in the Falls Road area of Belfast, when he was shot in the head with a rubber bullet on 20 April 1972. He was the first person to be killed by a rubber bullet during “The Troubles”; 16 more would follow, between 1972 and 1989. Eight of them were children. The young Rowntree died two days later of his injuries, which included skull fractures and lacerations of the brain. An inquiry into the killing was first launched in 2010, and the defendant, Soldier B., claimed he had no memory of having killed Francis Rowntree. The context was given that “a group of people were rioting and throwing stones at soldiers”, and it could not be established at the time whether Rowntree was in fact targeted or a victim of a richocheting bullet. After the inquiry took place and statements from the Coroner indicated excessive use of force, the family sued the Ministry of Defence – and Soldier B.’s statement sound much too familiar:

Virtually everybody you see were the target (…) The fact we are being pelted by just about every kind of missile, you are not really looking round to see if this person is innocent. I did not see a distinction.

Furthermore, statements from the Coroner, Brian Sherrard, include that there was no available training on the use of such weapons available to patrolling troops in the area:

The state provided Soldier B with a lethal weapon without notifying him of its potential lethality or training him in its use. (…) The absence of adequate training made it impossible for Soldier B to assess whether to use lethal force. (…) He fired without warning into the crowd, which was not aimed at any individual.

Francis Rowntree

The context of the use of LLWs in Northern Ireland matters. In a recent article written by Martin O’Flaherty, a parallel is drawn between the police force active in Northern Ireland at the time, the Royal Ulster Constabulary (RUC) and the militarized police departments active in the United States. While there is much to be learned about the non-negotiable demand to disband the RUC and build a new police force with inherent accountability mechanisms during the peace process, Northern Ireland was, at the time, under counter-insurgency and saw the deployment of armed troops, counter-terrorism unit, military intelligence, and covert counter-insurgency units, all of which were equipped with lethal weapons and granted powers that far exceed regular law enforcement. However, the use of rubber bullets here is still framed by international human rights law, and subjected to the same criteria of necessity and proportion; they were still fired in those cases as a means to disperse a crowd argued to engage in unlawful or threatening behavior.

And they still claimed lives.

While Northern Ireland painstakingly continues the difficult work to litigate unlawful killings from the conflict, the use of LLWs authorized by the British government by all its parties to the conflict on the ground – from the RUC to British armed forces – occurred with a vast array of injuries, if not deaths. The non-governmental organization Relatives for Justice, based in Derry and founded by families of victims, has long been an advocate to ban the use of rubber bullets as a display of excessive force. In a statement released in January 2007, responding to then Chief Constable Hugh Orde requesting the end of the use of rubber bullets for the purpose of public order or crowd control, the organization affirmed its position:

It is evident from the Chief Constable’s statement that the Plastic Bullet remains a lethal weapon in the armoury of the PSNI and the British Army. As a lethal weapon with devastating consequences plastic bullets, or any lethal replacement such as Tasers, are completely unacceptable and constitute a breach of international human rights standards. The most vulnerable in our society continue to be most at risk from these weapons – especially children. It is highly regrettable that the Chief Constable did not take this opportunity to completely end the use of the plastic bullet.

Based on painful existing experience, the former chief of the PSNI saw fit to end the use of plastic or rubber bullets, the risk of permanent injury or death when fired into a crowd – rendering it difficult to target a specific individual and to avoid certain parts of the body, as requested from the UN guidance – being too great. If there is no possibility for the use of force to be proportionate, it follows that it would be unlawful to use this weapon, especially when discharged against civilians, regardless of the lawfulness of the action in which they are engaged.

Opinion from P4HR

The US-based non-profit organization Physicians for Human Rights (P4HR) released a fact sheet on KIPs that would recommend a ban, due to blunt or penetrative trauma. While we’ve seen that the UN guidance recommends avoiding the head and torso, it is also nearly impossible to make that distinction in an order of dispersion and aiming at a crowd, especially if the police or armed forced are retreating due to action from the crowd. Aside from the injuries caused to the eyes and head, that have been documented, attention is drawn to musculoskeletal injuries, such as sprains, bruises, and fractures; KIPs can also cause “permanent damage to neurovascular structures”, leading to compartment syndrome. On skin and soft tissue, “superficial and deep lacerations may cause muscle and nerve damage as well as bleeding”. The numbers are staggering: research conducted by the organization over the past 25 years identifies 1925 individuals suffering injuries including 53 deaths and 294 permanent disabilities. 49% of those deaths resulted from direct strikes to the head, prohibited in the UN guidance, and 23% from blunt injury to the brain, spine, or chest, once again prohibited in IHRL recommendations but either not enforced due to lack of training or impossible to implement due to the situation in which they are use. 84% of injuries to the eyes resulted in permanent vision loss. In total, 70% of individuals struck by rubber bullets had severe injuries that required immediate medical assistance, that makes rubber bullets, for the sake of rhetoric, less lethal, but with a potential for morbidity and mortality that far exceeds what we expect law enforcement to be using against civilians in cases of unrest during peacetime.

Washington, DC. JOSE LUIS MAGANA/AFP VIA GETTY IMAGES)

Their 2016 report, Lethal in Disguise: The Health Consequences of Crowd-Control Weapons, released in conjunction with the International Network of Civil Liberties Organisations (INCLO), concluded unequivocally that KIPs are not incompatible with the human rights standards for crowd management and rubber-coated metal bullets specifically posed too much of a risk to be allowed to be used. Even alternatives to rubber bullets and pellets – like “sponge rounds”, that have a much lesser degree of penetration into the skin – must be used extremely sparingly. The diversity in KIPs, such as “bean bag rounds” and pellets, are inherently meant to create an injury significant enough to incapacitate individuals, and not for a short amount of time. The dispersion and the fear that can be caused by the firing of those weapons can also create a stampede that would be extremely dangerous for injured people who can’t move, are bleeding, and need to be removed from the crowd in ordered to receive medical attention.

IHRL going forward

Enforcing protections and safeguards against the violation of the prohibition of torture is one of the biggest challenging in international human rights law. Reservations to the very definition of torture and the threshold of cruel treatment differs much too often from what should be a universal standard. If we are to have a conversation on the role of law enforcement in open, democratic societies upholding the rule of law, as is currently the case, we must engage in the complex and painful work of examining whether law enforcement is indeed a protection of civilians, in which officers are tasked with the right of safety and the right to security, or if they are an instrument of state power under increased human rights restrictions. The encroachment of counter-terrorism on legitimate law enforcement activities has dug deep trenches between a population seeking change and addressing their representatives the way they are entitled, and a police force armed to the teeth using weapons that have the potential to permanently maim and kill. The fear that this causes especially when used against individuals due to bias – another human rights violation against ethnic minorities, LGBTQIA individuals, and human rights defenders – demand a much broader conversation on legitimacy of policing. The UN guidance, because it isn’t legally binding, and is subjected to the definitions that states uphold of necessity, proportionality, and precaution, is not sufficient and has not addressed the danger those weapons could pose in a climate of intense tension.

De-escalation requires minimizing police equipment; redirect the funding toward social justice programs and not the acquisition of more weaponry; and focus on training, sensibility to human and civil rights, and replacing law enforcement where it belongs, which is protection, not attack. A ban on rubber bullets could be a considerable advancement at a time when confrontation with police leads to injuries and death, even when those encounters were not meant to be violent. If we want to address police violence, we must address what enables this violence: theoretically with policy, and practically with powers.